NEW DELHI: The sudden visit by U.S. Special Representative Zalmay Khalilzad to Delhi and his meetings with Foreign Minister S Jaishankar and NSA Ajit Doval has set off speculation about India’s future role in Afghanistan. Within a day articles appeared that either suggested India would engage with the Taliban and even help push-start the peace negotiations or that India would continue to insist that the Taliban accept the Afghan Constitution and the legitimacy of the government of President Ghani before it engages with them.

The initial stand of the United States on ending the war in Afghanistan was articulated by Secretary Hillary Clinton early in the Obama years. It called upon the Taliban to abjure violence, accept the Afghan Constitution and enter into negotiations with the Government of Afghanistan. That went nowhere and was replaced with the ‘Afghan-owned, Afghan-led, Afghan-controlled’ peace process formula. The government of Manmohan Singh accepted this formulation. Therefore, any thoughts that the Taliban be first asked to accept the Afghan Constitution is a non-starter.

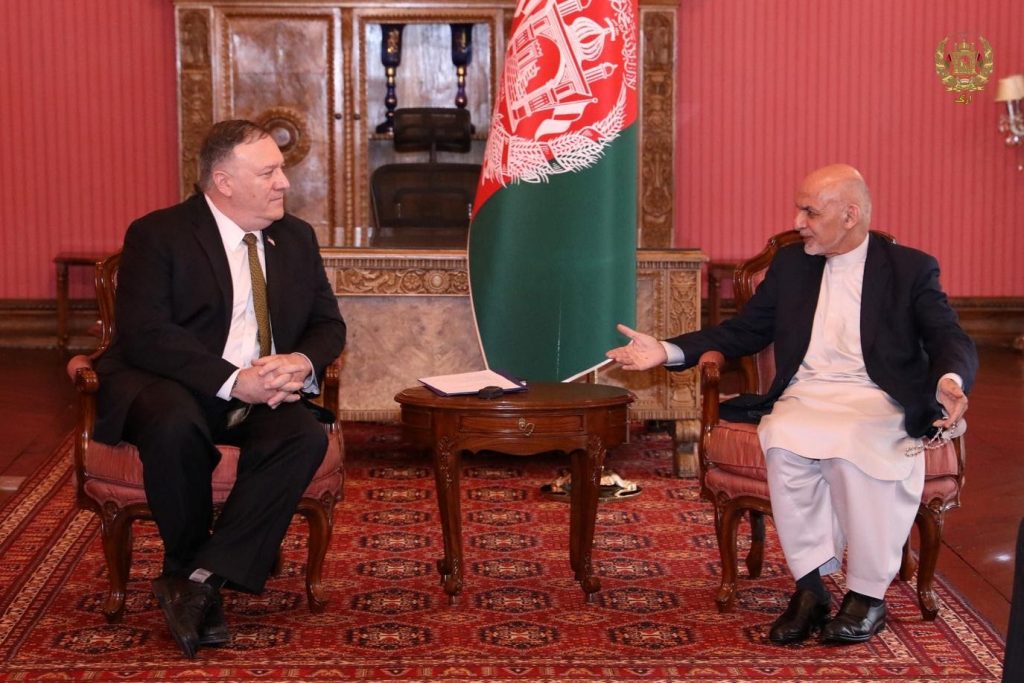

The reality on the ground is that the U.S. is withdrawing its troops, and that most of the cards are in the hands of the Taliban, who have emerged the Afghan player most international actors want to engage with. Their political office is based in Doha, paid for by Qatar. Their leaders travel to world capitals—Moscow, Beijing, Tehran and Jakarta for instance, and meet the world leadership. President Trump calls Mullah Baradar, the top Taliban negotiator, to discuss progress of the talks, leaving it to his officials to talk to Ghani. The United Nations and governments of countries, other than India, engaged with Afghanistan welcomed the Doha Agreement. Delhi too was present at the signing ceremony in Doha. Incidentally, the Doha Agreement binds the Taliban to enter into ‘intra-Afghan negotiations with Afghan sides’ to arrive at a ‘new post-settlement Afghan Islamic government’. Any ceasefire would only be part of such settlement. At no stage did the Taliban commit itself to negotiations with what they call the ‘Kabul regime’. In fact, the Government of Afghanistan is not even referred to in the Doha Agreement.

More than battlefield successes, it is the total collapse of democratic legitimacy that has weakened Kabul’s position. The Afghan people, in very large numbers, voted in the 2014 Presidential elections, at the cost of losing their fingers which bore the indelible ink. The Taliban had called for election boycott, threatened violence and occasionally carried it out. The Taliban stand was that the elections were a sham and that the ‘occupiers’ called the shots. The second round of elections was seriously flawed and almost led to a constitutional breakdown, saved only by heavy lifting by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry who forced a compromise. The resultant National Unity Government of President Ghani and Chief Executive Abdullah could deliver neither on good governance nor on carrying out necessary constitutional changes to move to a parliamentary system. Nor was any serious attempt made to ensure that future elections were free, fair and transparent.

The less said about the 2019 Presidential elections, the better. Insecurity, mismanagement and malfeasance meant that voting was low, and after removing ‘doubtful’ votes, Ghani was declared winner in the first round with just over 50 per cent of the votes. Overall, he polled less than one million votes in a country of around 35 million. Abdullah rejected the vote count, declared himself winner; both contenders arranged parallel swearing-in ceremonies. Failure of the Afghan political class to get its act together led to the U.S. threat to reduce assistance by US $1 billion. This and the general lack of credibility have forced the two rivals, Ghani and Abdullah, to resume negotiations.

This failure of the Afghan political class has meant that it has not only lost credibility, which was always shaky, but also its legitimacy. Consequently, almost the entire Afghan political class, other than Ghani, has met Taliban representatives in peace conferences in different settings. They all accepted the Taliban’s condition that these worthies were present in their individual capacities only since the latter does not recognise the Afghan Constitution or the government of Afghanistan. Ghani has simply been unable to meet them but not for lack of trying. He recognises the Taliban but they have not acknowledged his legitimacy.

India has been upset with the U.S. for using the services of Pakistan in order to get out of Afghanistan. Pakistan’s perfidy is not a secret anymore. However, a look at the map would explain that the U.S. has no option. Worse, it is Pakistan which has been the main backer of the Taliban. Indian analysts should understand that the U.S. would no longer be dependent on Pakistan once its troops are home. It is also useful to remember that India and the U.S. are not treaty allies. It has taken India long to even sign foundation agreements with the United States. Trump’s discussions with PM Modi during the former’s visit to India and Khalilzad’s meetings are an indication that the two countries are engaging seriously on Afghanistan. It is not that the U.S. needs India to intervene with different Afghan factions since India has not been in the game since the fall of the Taliban nor has it been directly involved in Afghan politics.

In Afghanistan, India is generally seen as a reliable partner that does not take sides but there is lingering suspicion among some that India would like a resurrected Northern Alliance to dominate the political landscape. These doubts that flow out of Pakistan should be disabused. In any case, no such resurrection is possible as the leaders of the erstwhile Northern Alliance are scattered across the political spectrum, including important ones with Ghani. However, historically, whosoever takes power in Kabul, whether it was the Mujahideen in 1996 or Ghani in 2014, comes around to appreciating India as a valued partner. Unspoken is the need for a friendly India to allow Kabul to exercise agency vis-à-vis Pakistan.

The world is suffering from an ‘Afghanistan fatigue’. That country would require considerable foreign assistance but, in the changed situation, even before Covid-19, it is unlikely to get the resources it got earlier. India’s development assistance spread across the country is much appreciated by all sides. Even though India cannot compensate Afghanistan for the loss in foreign assistance from the West, India’s efforts are more cost-effective and relevant.

The memories of IC-814 still seem to linger in the minds of Indian analysts and establishment twenty years after that Pakistani-sponsored assault on India. For India, the Taliban is seen as a proxy of Pakistan, but the picture is not so black and white. Pakistan has been Taliban’s major backer and gives it safe haven. But it does not trust them completely. Pakistani military officers are present in Taliban meetings and in their operations rooms. The families of Taliban leadership are kept in custody; if the family has to travel, the leader has to surrender and be kept hostage. And when Karzai opened up to the Taliban in 2010 and Mullah Baradar reciprocated on the latter’s behalf, he was arrested by Pakistan on a trumped-up charge and remained in custody till 2018. The rise of Mullah Baradar and his relocation to Qatar should be seen in proper perspective.

India does have legitimate fears about a Taliban-dominated regime in Afghanistan, given the group’s past history and dependence on Pakistan. Pakistan would be uncomfortable with any forward movement on India-Taliban engagement but that is to be expected. It would do everything possible to sabotage it, including spreading the fear that its own proxies, the LeT and Jaish, are now relocating to Afghanistan. For India, the only way forward is to talk to the Taliban at present, before it is part of the formal governing arrangement, as India does with the entire Afghan political spectrum. The Taliban should be made aware of India’s concerns so that there could be an effort at finding a meeting ground. India does have considerable equity that would help arrive at diminishing areas of divergence.

The Taliban have not given any anti-India statement since 2001. They have, in fact, publicly said they would like India as a development partner of Afghanistan and have not attacked India-funded projects. After India revoked the special status to Jammu & Kashmir on August 5 last year, the Pakistani Foreign Minister issued a statement threatening breakdown in Afghan peace negotiations but the Taliban publicly contradicted him, saying there was no link between Kashmir and Afghanistan. Should India then continue to live in the past? Can India move beyond IC-814? It must also be remembered that unlike the last time, the Taliban are not friendless. It is also triumphant, having defeated a superpower. Wouldn’t they like to exercise political independence? And can India continue to work with Afghanistan so that the latter can exercise sovereignty independently?

India must ride the tide at its flood and not wait, lest it gets stuck in shallows and miseries.

(The author is Director of Atal Bihari Vajpayee Institute of Policy Research and International Studies, Maharaja Sayajirao University, Vadodara, India. Views expressed in the article are personal.)

[/vc_column][/vc_row][/tdc_zone]